Ritalin 曾經是“奶奶的小幫手”

1966 年的廣告顯示利他林曾經被推銷為一種給家庭主婦使用的“精神抗抑鬱劑”

2015 年 12 月 7 日

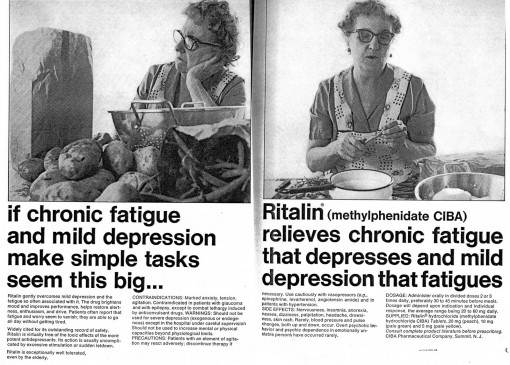

尤金·雷克爾(Eugene Raikhel)揭示了 1966 年的一則廣告,當時利他林(Ritalin),如今主要用於治療 ADHD,曾被推銷為一種針對家庭主婦的“精神抗抑鬱劑”。他寫道:“我還發現,與當代抗抑鬱藥物的廣告不同,這則廣告中的女性在‘服用後’的畫面中看起來並不特別快樂。她只是在默默地剝蔬菜,履行她的家庭主婦職責,看起來幾乎和‘服用前’一樣痛苦。這不禁讓人聯想到自 90 年代以來針對 ADHD 的利他林批評:它被用作培養自我約束能力的工具,讓人們能夠履行社會所期望的角色。”

文章來源:https://www.madinamerica.com/2015/12/ritalin-used-to-be-grandmas-little-helper/

Eugene Raikhel reveals ads from 1966 where Ritalin, now prescribed largely for ADHD, was marketed as a “kind of mind antidepressant for housewives.” “I also find striking that—unlike what you find in contemporary ads for anti-depressants—the woman in this ad doesn’t look particularly happy in the ‘after’ shot. She’s just steadily peeling away, fulfilling her housewifely duties, looking almost as miserable as she does in the first image. It almost lends itself too easily to the critique made of Ritalin in connection to ADHD since the 90s: that it is used as a means of fostering self-disciplining subjects capable of fulfilling expected social roles.”

奶奶的小幫手

我在 1966 年的 JAMA 期刊中看到這則廣告。這並不是我研究的領域,但我認為這則廣告頗具啟發性,反映了過去三十年來精神病學和心理健康護理領域發生的變化。

現在我們認為利他林(Ritalin)是一種用來抑制多動或集中 ADHD 兒童異常分散注意力的藥物,因此看到它當時被推銷為一種給家庭主婦使用的輕微抗抑鬱藥,這非常引人注目。鑑於該藥物是一種興奮劑,這其實是合情合理的。正如多篇有關 ADHD 歷史的研究所指出的那樣,興奮劑如苯丙胺(Benzedrine)在鎮靜多動兒童(在 1960 年代常用的診斷術語是“多動症候群”)方面的有效性,讓臨床醫生感到驚訝且反直覺。

該廣告還使用了模糊的 DSM-III 前診斷語言:“抑鬱導致的慢性疲勞和疲勞引起的輕度抑鬱”!

我還發現,與當代抗抑鬱藥物廣告不同的是,廣告中的女性在“服用後”的畫面中並沒有看起來特別快樂。她只是默默地剝皮,履行著家庭主婦的責任,看起來幾乎和“服用前”一樣痛苦。這不禁讓人聯想到自 90 年代以來針對 ADHD 的利他林批評:它被用作培養自我約束能力的工具,讓人們能夠履行社會期望的角色。

安迪·拉科夫(Andy Lakoff)和伊麗娜·辛格(Ilina Singh)都撰寫了有關 ADHD 作為診斷實體發展的報告,辛格在《科學與背景》(Science in Context)中的文章很好地解釋了早期針對女性的利他林推廣如何為其後來用於兒童鋪平了道路:

「Ciba 通過付費的臨床研究、醫師期刊上的廣告和直接銷售策略,在醫學行業內推廣利他林方面發揮了重要作用……要確定 Ciba 在推動利他林在家庭領域接受度方面的作用則更為困難。可以推測的是,利他林受益於公共對精神疾病理解的轉變,部分原因是針對‘擔心健康人群’創造和推銷藥物。特別是抗抑鬱藥物的成功可能促使母親們接受利他林來治療男孩相對常見的行為問題。製藥業和醫學界可能將抗抑鬱診斷和治療的目標對準了女性……習慣於使用藥物來解決自己常見問題的女性,可能更容易接受利他林來解決她們兒子的問題。」(Singh 2002: 592-593)

關於 ADHD 的更多歷史資料,請參見:

Lakoff, A. “Adaptive Will: The Evolution of Attention Deficit Disorder.” Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 36, 2 (2000): 149-169.

Singh, I. “Bad Boys, Good Mothers, and the “Miracle” of Ritalin.” Science in Context 15, 04 (2002): 577-603.

MAD IN TAIWAN備註:

Ciba 是一家瑞士的製藥和化學公司,全名是 Ciba-Geigy。該公司成立於 1970 年,實際上是由兩家公司——Ciba 和 Geigy——合併而來。Ciba 曾經是全球製藥領域的重要參與者,尤其是在推廣利他林(Ritalin)這類藥物方面。

Ciba 起初是一家染料公司,後來逐漸進軍化學和製藥領域,並成為研發和推廣藥品的主要企業之一。利他林(哌甲酯,methylphenidate)就是 Ciba 開發並推向市場的藥物,最初是作為一種興奮劑使用,後來被用來治療 ADHD。

1996 年,Ciba-Geigy 與 Sandoz 合併,成立了 諾華公司(Novartis),這也是當今全球最大型的製藥公司之一。

Grandma’s little helper

I came across this ad in a 1966 issue of JAMA. This isn’t at all my area of research, but I thought the ad was quite evocative of the changes that have occurred in psychiatry and mental health care over the past thirty years.

Because we now think of Ritalin as a drug used to curb hyperactivity or to focus the abnormally dispersed attention of ADHD kids, it is striking to see that at this time it was being marketed as a kind of mild anti-depressant for housewives. Given that the drug is a stimulant, this makes sense, and as several accounts of the history of ADHD have pointed out, it was originally the effectiveness of stimulants like Benzedrine in calming hyperactive children (during the 1960s the diagnostic term often used was “hyperkinetic syndrome”) that clinicians found surprising and counterintuitive.

The ad also uses a vague pre-DSM-III diagnostic language: “chronic fatigue that depresses and mild depression that fatigues,”!

I also find striking that—unlike what you find in contemporary ads for anti-depressants—the woman in this ad doesn’t look particularly happy in the “after” shot. She’s just steadily peeling away, fulfilling her housewifely duties, looking almost as miserable as she does in the first image. It almost lends itself too easily to the critique made of Ritalin in connection to ADHD since the 90s: that it is used as a means of fostering self-disciplining subjects capable of fulfilling expected social roles.

Andy Lakoff and Ilina Singh have both written accounts of the development of ADHD as a diagnostic entity, and Singh’s article in Science in Context gives us a nice interpretation of how this early marketing of Ritalin to women may have paved the way for its use with children:

“Ciba played an important role in the promotion of Ritalin within the medical industry through paid clinical research, advertising in physicians’ journals, and direct sales strategies…. It is more difficult to establish Ciba’s role in promoting acceptance of Ritalin within the domestic realm. It can be argued, speculatively, that Ritalin benefited from a shift in public understanding of mental illness, promoted in part by the creation and marketing of drugs for a nation of “worried well.” In particular, the success of anti-depressant drugs may have contributed to mothers’ acceptance of Ritalin for relatively common behavior problems in boys. The pharmaceutical industry and the medical profession probably targeted women for anti-depressant diagnoses and treatments… and women accustomed to drugs for their own relatively common problems may have been more likely to accept Ritalin for their sons’ problems,” (Singh 2002: 592-3)

For more on the history of ADHD see: