莎拉·克努森-2018 年 4 月 1 日

我目前的診斷是“I型雙相情感障礙”。幾年後,這可能不會存在。我甚至可以起訴我的臨床醫生沒有評估或排除與傳統診斷特徵重疊的已知壓力生物標誌物。

My current diagnosis is “Bipolar I Disorder.” In a few years, that likely won’t exist. I might even be able to sue my clinician for not assessing — or ruling out — known biological markers of stress that overlap with conventional diagnostic features.

下面是它的工作原理。

Here is how it works.

我們現在對壓力模型的了解

What we now know about the stress model

由於各種複雜的原因,我們中的一些人在生命早期就形成了過度活躍的壓力基線(同情/戰鬥或逃跑反應)。這是斯坦福大學世界著名的神經生物學家和靈長類動物學家羅伯特·薩波爾斯基(Robert Sapolsky)的卑鄙和骯髒:

For a variety of complicated reasons, some of us develop an overactive stress baseline (sympathetic/fight-or-flight response) early on in life. Here’s the down and dirty from Robert Sapolsky, world-renowned neurobiologist and primatologist at Stanford University:

在眾多物種中,主要的早期生活壓力源會導致兒童和成人的糖皮質激素水平升高(以及 CRH 和 ACTH,調節糖皮質激素釋放的下丘腦和垂體激素)和交感神經系統的過度活躍。32 基礎糖皮質激素水平升高——壓力反應總是被激活——並且在壓力源後恢復到基線的延遲。麥吉爾大學的邁克爾·米尼 (Michael Meaney) 展示了早期生活壓力如何永久削弱大腦控制糖皮質激素分泌的能力。(薩波爾斯基,2017 年,第 194-95 頁。)1

Across numerous species, major early-life stressors produce both kids and adults with elevated levels of glucocorticoids (along with CRH and ACTH, the hypothalamic and pituitary hormones that regulate glucocorticoid release) and hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system. 32 Basal glucocorticoid levels are elevated—the stress response is always somewhat activated—and there is delayed recovery back to baseline after a stressor. Michael Meaney of McGill University has shown how early-life stress permanently blunts the ability of the brain to rein in glucocorticoid secretion. (Sapolsky, 2017, pp. 194-95.)1

一種簡單的思考方式是,我們中的很多人都以“高空閒(high idle)”模式開始生活。為了自己的利益,引擎總是有點太快了,而且運行得有點快。另外,比平時更難平靜下來。這增加了系統的磨損,並且多年來開始顯現。

A simple way of thinking about this is that a lot of us start our lives in ‘high idle’ mode. The engine is always a little too revved and running a bit fast for its own good. Plus, it’s harder than usual to calm it down. This puts added wear and tear on the system, and that begins to show over the years.

高轉速的影響可以通過無數種方式體現出來。壓力反應幾乎影響人類功能的各個方面。以下是 Sapolsky (2004) 2在另一本書中討論的一些內容:

There are a zillion ways the effects of a high rev can manifest. The stress response affects virtually every aspect of human functioning. Here are some that Sapolsky (2004)2 discusses in another book:

- 腺體、激素、神經遞質的功能

- 心臟、血壓、膽固醇、呼吸

- 新陳代謝、食慾、消化、胃和腸道功能

- 增長與發展

- 性與生殖

- 免疫系統,易患疾病

- 疼痛

- 記憶

- 睡覺

- 衰老與死亡

- 心理健康和福祉

- “抑鬱”,動機,體驗快樂的能力

- 性格與氣質

- 容易上癮

- Functioning of glands, hormones, neurotransmitters

- Heart, blood pressure, cholesterol, breathing

- Metabolism, appetite, digestion, stomach and gut functioning

- Growth and development

- Sex and reproduction

- Immune system, vulnerability to disease

- Pain

- Memory

- Sleep

- Aging and Death

- Mental health and well-being

- “Depression,” motivation, ability to experience pleasure

- Personality and temperament

- Vulnerability to addiction

換句話說,在人類的思想和身體中,幾乎沒有什麼事情不會受到壓力反應的潛在影響。

In other words, there’s practically nothing that happens in human minds and bodies that the stress response doesn’t potentially affect.

壓力反應如何影響我們個人是另一回事。人類在我們的生活環境、經歷、興趣和天賦上有著難以置信的多樣性。生活沒有手冊。也沒有一種正確的做事方式。相反,人類發展更多是一種創造性的努力。

How the stress response affects us individually is a different matter. Human beings are incredibly diverse in our life circumstances, experiences, interests and gifts. There is no manual for life. Nor is there any one right way of doing things. Rather, human development is more of a creative endeavor.

我們每個人都會根據我們當時必須與之合作的內容(個人、社會、環境)來構建對我們面臨的挑戰的回應。隨著時間和重複,一些反應開始比其他反應更自然。他們開始覺得自己是“我”的本質。而且,很可能,我想出的東西——以及最終對我來說完全自然的東西——最終會與你想出的東西和最終對你感覺自然的東西完全不同。

Each of us constructs a response to the challenges we face based on what we have to work with (personally, socially, environmentally) at the time. With time and repetition, some responses start to come more naturally than others. They start to feel like the essence of ‘me.’ And, in all likelihood, what I come up with — and what ends up feeling entirely natural to me — will end up being entirely different from what you come up with and what ends up feeling natural to you.

這就是生活的美麗和多樣性。它可能給我們很多相互學習的機會。

That’s the beauty and diversity of life. It potentially gives us a lot to learn from each other.

那麼“躁狂症”到底是怎麼回事?

So what’s going on with ‘mania’?

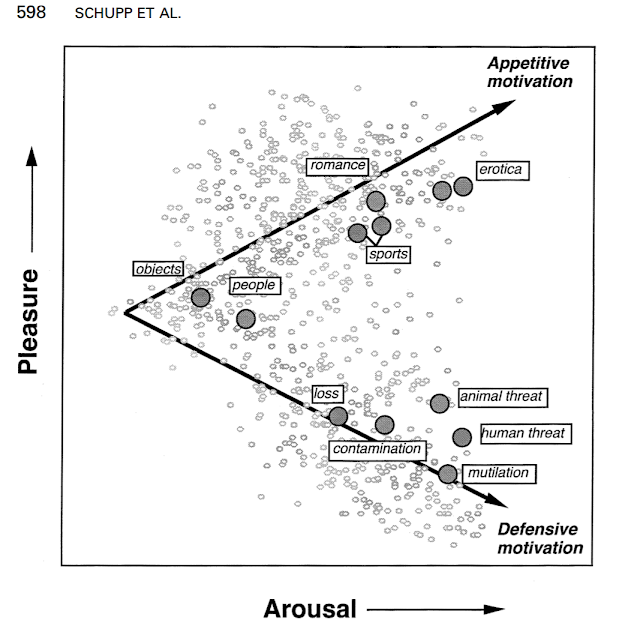

嗯,這是一個非常有趣的信息。事實證明,人類的壓力反應(同情/戰鬥逃跑)是一個真正的搖擺不定的人。它為兩支球隊效力。換句話說,壓力反應不只是被恐懼所激發,就像我被熊追趕一樣。如果我是熊 並追著你,它也會打開 。這是佛羅里達大學的一群研究人員發現的。(Bradley et al. 2001; 3 Bradley et al., in press; 4 Lang et al. 2010; 5 Lang et al. 2013; 6 Schupp et al. 2004. 7)這是他們繪製的一張圖表來說明什麼他們發現:

Well, here’s a really interesting piece of information. As it turns out, the human stress response (sympathetic/fight-flight) is a real swinger. It plays for both teams. In other words, the stress response doesn’t just get turned on by fear, like if I’m being chased by a bear. It also turns on if I am the bear and chasing you. This was discovered by a bunch of researchers at the University of Florida. (Bradley et al. 2001;3 Bradley et al., in press;4 Lang et al. 2010;5 Lang et al. 2013;6 Schupp et al. 2004.7) Here is one of the diagrams they drew to illustrate what they found:

(Schupp et al., 2010, p. 598.)

正如你所看到的,壓力反應(食慾動機)的好處與我們許多人在所謂的“狂躁”時傾向於追求的令人興奮和愉快的事情有很多重疊。

As you can see, the upside of the stress response (appetitive motivation) has a lot of overlap with the exciting and pleasurable things that many of us tend to chase after when we’re so-called ‘manic.’

當您考慮它時,它是有道理的。

When you think about it, it makes sense though.

人類的壓力/生存反應(交感神經系統/戰鬥飛行)旨在幫助我們生存——無論是作為個體還是作為一個物種。我們的生存不僅僅是盡可能快地擺脫威脅。生存還要求我們保持警惕,並在球上尋找潛在的機會。

The human stress/survival response (sympathetic nervous system/fight-flight) developed to help us survive — both as individuals and as a species. Our survival is not just about getting away from threats as fast as we can. Survival also requires us to be alert and on the ball for potential opportunities.

僅僅知道有機會是不夠的。很多機會都只是一瞬間。就像經典的貓捉老鼠一樣,你必須在它離開之前做好準備並追趕它。

It’s not enough to just know there’s an opportunity. A lot of opportunities are only there for a moment. Like classic cat and mouse, you have to gear up and go after it before it gets away.

想想黑色星期五在沃爾瑪的廉價購物。如果我要在大屏幕電視上搶購熱賣,我必須能夠非常迅速地動員起來。幸運的是,我的生存反應在那裡。一切都是對人類最重要的東西——從而使我能夠超越或擊敗下一個與我在同一個沃爾瑪討價還價的人。

Think of bargain shopping at Walmart on Black Friday. I have to be able to mobilize really quickly if I’m going to snatch up that hot deal on a big screen TV. Fortunately, the survival response is there for me. It’s all over the stuff that matters to human beings the most — thereby enabling me to out-hustle or out-wrestle the next guy who is all over the same Walmart bargain that I am.

“躁狂症”的生理學:症狀的症狀

Physiology of “Mania”: Symptom by symptom

既然我們對正在發生的事情有了一個基本的概述,讓我們來看看所謂的“狂熱”。我們將逐個檢查“躁狂發作”症狀的標準,以便您了解壓力反應在此處可能如何發揮作用。

So now that we have a basic outline of what’s going on, let’s take a look at so-called ‘mania.’ We’ll go through the criteria for a ‘manic episode’ symptom by symptom so you can see how the stress response is potentially operating here.

DSM 5 躁狂發作標準

DSM 5 Criteria for Manic Episode

A) 一段明顯的異常和持續升高、膨脹或易怒的情緒,以及異常和持續增加的目標導向活動或能量,持續至少 1 週,並且幾乎每天都出現(或任何持續時間,如果住院是必要的。

B)在情緒障礙和精力或活動增加期間,以下症狀中的三個(或更多)(如果情緒只是煩躁,則四個)顯著存在並且代表與通常行為的明顯變化:

1. 誇大的自尊或自大。

2. 睡眠需求減少(例如,僅睡 3 小時後感覺休息)。

3. 比平時更健談或有繼續說話的壓力。

4. 思想飛馳而過的想法或主觀體驗。

5. 報告或觀察到的分散注意力(即,注意力太容易被不重要或不相關的外部刺激所吸引)。

6. 目標導向活動(社交、工作或學校,或性)或精神運動激動(即無目的

的非目標導向活動)增加。

7. 過度參與可能導致痛苦後果的活動(例如,無節制地

瘋狂購買、性行為不檢或愚蠢的商業投資)。

DSM 5 Criteria for Manic Episode

A) A distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood and abnormally and persistently increased goal-directed activity or energy, lasting at least 1 week and present most of the day, nearly every day (or any duration if hospitalization is necessary.

B) During the period of mood disturbance and increased energy or activity, three (or more) of the following symptoms (four if the mood is only irritable) are present to a significant degree and represent a noticeable change from usual behavior:

1. Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity.

2. Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep).

3. More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking.

4. Flights of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing.

5. Distractability (i.e., attention too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant external stimuli), as reported or observed.

6. Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or sexually) or psychomotor agitation (i.e., purposeless

non-goal-directed activity).

7. Excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained

buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments).

讓我們首先從標準 A 開始:情緒高漲、膨脹或易怒、精力增加、目標導向活動增加。

Let’s start with Criteria A first: elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, increased energy, increased goal-directed activity.

要真正了解發生了什麼,讓我們回到沃爾瑪的討價還價,看看身體和精神上發生了什麼:

To really see what’s going on, let’s go back to that Walmart bargain and take a look at what is happening physically and mentally:

- 首先,這樣的機會不會每天都來。

- 很有可能,我會以我最終能負擔得起的價格得到我迫切想要的東西。

- 但有一個問題:當且僅當我想要的商品還在貨架上時,我才能買到便宜貨——這需要我瘋狂地激活才能擊敗下一個人。

- First of all, an opportunity like this doesn’t come every day.

- In all likelihood, I’m gonna get something I desperately want at a price I can finally afford.

- But there’s a catch: I get the bargain if and only if the item I want is still on the shelf — which requires me to activate like crazy to beat out the next guy.

那麼我的情緒是膨脹的還是高漲的……?你打賭。這是一年的機會,我可能會得到它。

So is my mood expansive or elevated…? You bet. It’s the chance of a year, and I might get it.

我會不會被激怒……?好吧,如果有什麼東西打斷我或妨礙我,你打賭。

Am I going to get potentially irritated…? Well, if anything cuts me off or gets in my way, you bet.

我的能量增加了嗎……?你打賭。我必須為它衝刺。

Is my energy increased…? You bet. I have to make a dash for it.

我是目標導向的……?你打賭。這就是全部目的。

Am I goal-directed…? You bet. That’s the whole purpose.

會持續一周嗎……?可能不會,因為這是一日特賣。

Does it last a week…? Probably not, because it’s a one-day sale.

但它可以。就像我必須在倖存者秀中與其他客戶競爭以獲得最好的交易的機會——而這種競爭持續了一周或一個月……那麼,如果我真的、真的想要那個項目,那就是我的一次機會,我很可能會一直保持活力,只要給自己最好的機會來獲得獎品。而且,就像我在戰區必須保持高度戒備一樣,我的身體很可能會在需要的時候升起,以盡可能地保護自己的利益。

But it could. Like if I had to compete with the other customers in a survivor show for the chance to get the best deal — and that competition went on for a week or a month… Well then, if I really, really wanted that item, and this was my one chance, I might well stay revved for as long as it took to give myself the best chance I could at landing the prize. And, just the same as if I was in a war zone and had to stay in high alert, my body would likely rise to the occasion for as long as I needed it to in order to protect my interests as much as possible.

好的,進入標準 B。在這裡,您必須更多地了解戰鬥或逃跑反應以及它如何實際影響我們。當我追逐千載難逢的機會時,我的身體會這樣做:

Okay, on to Criteria B. Here’s where you have to understand a bit more about the fight or flight response and how it actually affects us. When I’m chasing the opportunity of a lifetime, this is what my body does:

- 腎上腺素飆升。我的心臟跳動,肺泵和血壓放大器。所有這些都是為了讓我的肌肉盡可能多地獲得燃料和氧氣。

- 我的頭髮直立,我的拳頭緊握,我的腿準備好奔跑。一切都準備好了,隨時準備好突襲。

- 我的消化功能停止了。我的胃變得噁心和輕盈。我的膀胱和腸子排空——只是為了確保沒有多餘的多餘物質阻礙我。

- 高階思維(判斷)被擱置。這需要我的肌肉移動我所需的能量。它也需要很長時間。這是採取行動的時候了!我不能沉迷於細節。一旦貓在袋子裡,就會有足夠的時間對可能的不同之處進行更仔細和反思的評估。

- 排除了判斷力,就會出現快速反應和舊習慣。自主系統在幕後接管並開始調用戲劇。無論我最擅長和最了解的是什麼——最自然的事情——都是該系統所配合的。畢竟,賭注很高。這是我生命中的超級碗。我不會嘗試新的四分衛或新的打法。我也不打算輸入第二個字符串。沒門!在這種心態下,我已經做了無數次的事情將再次完成。

- 接下來是隧道視野和隧道聽力,以排除所有外部干擾。注意鉚釘。這讓我能夠高度專注並完全放大我對我想要發生的事情的看法。

- 我不覺得痛。字面上地。內啡肽,我身體的天然阿片類藥物,現在全速運轉,再次確保沒有任何東西會分散我手頭的任務。

- 它變得更好。我追求一個非常有意義的個人目標的事實給了我大量的多巴胺——這本質上是內源性的可卡因。換句話說,我得到了身體自身獎勵系統的鼓勵和強化,全心全意地追求我非常關心的事情。

- Adrenaline surges. My heart pounds, lungs pump and blood pressure amps. All of this is in service of getting as much fuel and oxygen to my muscles as possible.

- My hair stands on end, my fists clench, my legs get ready to run. Everything is primed and ready to pounce at the drop of a hat.

- My digestion shuts down. My stomach gets queasy and light. My bladder and bowels empty — just to make sure there’s no needless surplus holding me back.

- Higher-order thinking (judgment) gets put on hold. That takes energy that my muscles need to move me. It also takes wayyyyy too long. This is a time for action! I can’t afford to get bogged down in details. Once the cat is in the bag, there will be plenty of time for a more careful and reflective appraisal of what could be different.

- With judgment out of the way, out come the fast reflexes and old habits. The autonomic system takes over behind the scenes and starts calling the plays. Whatever it is that I do best and know best — whatever comes most naturally — is what that system goes with. After all, the stakes are high. This is the Superbowl of my life. I’m not going to try out a new quarterback or a new play. I’m also not going to put in the second string. No way! It’s the stuff I’ve already done a zillion times over that is going to get done once again in this frame of mind.

- Next come the tunnel vision and the tunnel hearing to shut out all the outside distractions. Attention rivets. This allows me to hyper-focus and totally zoom in on my vision of what I want to happen.

- I feel no pain. Literally. Endorphins, my body’s natural opioids, are in full gear now, again making sure that nothing distracts me from the task at hand.

- It gets even better. The fact that I’m pursuing a highly meaningful personal goal is giving me massive hits of dopamine — which is essentially endogenous cocaine. In other words, I’m getting encouraged and reinforced by my body’s own reward system to wholeheartedly pursue something I care about a lot.

好的,現在讓我們回到標準 B。

Okay, now let’s go back to Criteria B.

1. 誇大的自尊或自大。我在這裡感覺很強大嗎?你打賭。一生的機會在合理的範圍內。我的肌肉被抽了。我不覺得痛。我得到了巨大的內部獎勵。內源性可卡因告訴我我做得很好。任何可能阻止我的外部反饋都被排除在外。是的,這個空間感覺非常棒。如果我也不是很了不起,那我為什麼會在這裡?

1. Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity. Am I feeling pretty powerful here? You bet. An opportunity of a lifetime is within reasonable reach. My muscles are pumped. I’m feeling no pain. I’m getting massive internal rewards. Endogenous cocaine is telling me I’m doing great. Any outside feedback that could discourage me is being shut out. Yep, this space feels pretty awesome. And if I weren’t pretty awesome too, then why would I be here?

2. 睡眠需求減少。說實話。在這種情況下,我的身體到底有沒有機會讓我睡覺……?

2. Decreased need for sleep. Let’s be honest. Is there any chance in hell my body is going to let me sleep in these circumstances…?

3. 比平時更健談或有繼續說話的壓力。是的,當然。如果我在乎你或你在乎我,你敢打賭我在說。這是千載難逢的機會。我想讓你知道。我想讓你參與進來。我希望得到你 100% 的支持。這太珍貴了,我們誰都不能錯過。而且,我會確保你知道這一點。我還將確保您獲得幫助該計劃成功所需的所有信息。哎呀,如果我下去,你甚至可以在沒有我的情況下進行。

3. More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking. Yep, for sure. If I care about you or you care about me, you bet I’m talking. This is the opportunity of a lifetime. I want you to know about it. I want you to get in on it. I want your support 100%. This is way, way, way too precious for either of us to miss out on. And, I’m gonna make sure you know that. I’m also going to make sure you have all the information you need to help this plan succeed. Heck, you can even carry it out without me if I go down.

4.想法的飛行,思緒飛馳。你打賭。有很多東西要弄清楚,有很多角度要預測。必須考慮所有可能性。必須預見和解決所有漏洞。

4. Flights of ideas, racing thoughts. You bet. There’s so much to figure out and so many angles to anticipate. All possibilities must be considered. All vulnerabilities must be anticipated and addressed.

5. 分心。坦率地說,我可能再也不會感覺這麼好了。我很順利,我最好利用這種能量,而它在這裡。沒有一刻可以失去。我需要確保在宇宙對我如此慷慨並讓我感覺如此美妙的同時,我得到了我可能得到的一切。是的,我知道你可能認為你有重要的事情要對我說。但這可以等待。我們可以隨時交談。你不明白。 這是千載難逢的機會。

5. Distractability. Frankly, I might never feel this good again. I’m on a roll and I better take advantage of this energy while it’s here. There’s not a moment to lose. I need to make sure that I get everything I can possibly get while the universe is being this generous to me and making me feel this amazingly great. Yes, I know you might think you have important things to say to me. But that can wait. We can talk anytime. You don’t understand. This is a once in a lifetime opportunity.

6. 以目標為導向的活動,精神運動性激越。是的。這是肯定的,就像我們上面談到的那樣,出於上述所有原因。

6. Goal-directed activity, psychomotor agitation. Yep. This is here for sure, like we talked about above, for all the reasons above.

7. 風險活動,很可能造成痛苦的後果(無節制的購買狂潮、性行為不檢或愚蠢的商業投資)。確切地。這就是生存反應真正如此致命的地方。

7. Risky activities, high potential for painful consequences (unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments). Exactly. This is where the survival response is really so deadly.

事實上,生存反應的全部目的是促進快速行動和快速解決。所以它基本上是在告訴我,一切都很緊迫,跑,跑,跑。因為,這畢竟是千載難逢的 機會。 所以,把它釘下來,現在。一旦我們掌握了它,之後就會有足夠的時間來思考我們做了什麼,我們是如何做到的,下次如何做得更好。但是,我的大腦在生存的心態中說, 現在不是時候。

In simple fact, the whole purpose of the survival response is to facilitate quick action and fast resolution. So it’s basically telling me that everything is urgent and to run, run, run. Because, after all, this is the opportunity of a lifetime. So, nail it down, right now. Once we have it in hand, there will be plenty of time afterward to think about what we did, how we did it, how it might go better next time. But, says my brain in the survival frame of mind, this is not the time.

在這種情況下,我更好的判斷真的沒有機會了。與此同時,我的身體已經準備好採取行動,而我的舊習慣得到了自由支配,但同時資源不足。任何外部反饋通過高強度隧道視覺/隧道聽覺超聚焦系統巡邏的防火牆的可能性也很小,該系統熱衷於確保我 100% 的注意力都集中在追求這個獎勵上。

In these circumstances, my better judgment really doesn’t have a chance. It’s under-resourced at the same time that my body is primed for action and my old habits are given a free reign. There’s also very little chance of any outside feedback getting past the firewall that is being patrolled by the high intensity tunnel vision/tunnel hearing hyper-focus system that is keen to insure that 100% of my attention is focused on pursuing this reward.

這樣就可以了。免除了所謂的遺傳、化學失衡的“躁狂症”的所有症狀,只有每年感恩節都會發生在數百萬美國人身上的小花園式的人類壓力反應。

So that about does it. Dispensed with all the symptoms of so-called genetic, chemically-imbalanced ‘mania’ armed only with the little ole garden-variety human stress response that happens for millions of Americans every Thanksgiving.

如果你到目前為止一直在關注我,並將其與你自己的經歷聯繫起來,那麼你很可能開始看到所有這些如何結合在一起,創造出被標記為“躁狂發作”的“完美風暴”。

If you’ve been following me so far, and relating it to your own experience, then quite possibly you’re beginning to see how all of this might come together to create the ‘perfect storm’ that gets labelled a ‘manic episode.’

但是,在所謂的“狂熱”之後不可避免的崩潰呢?那是從哪裡來的?

But what about that inevitable crash that comes after the so-called ‘mania’? Where does that come from?

小菜一碟。生存反應依賴於借來的時間和精力。它需要各種其他身體系統的犧牲。當時,我不知道會發生這種情況。腎上腺素、能量激增、多巴胺衝擊、止痛藥、超專注的心態都匯聚在一起,讓我追逐短期收益。

Piece of cake. The survival response runs on borrowed time and energy. It requires sacrifice from all sorts of other bodily systems. At the time, I have no idea this is happening. The adrenaline, the power surge, the dopamine hits, the pain killers, the hyper-focus frame of mind all converge to keep me chasing short-term gains.

然而,一旦我回到地球,就是回報的時候了。有一大堆加油、補充和損壞修復必須完成——至少在我自己的身體裡,很可能在我的生活中也是如此。

Once I come back to earth, however, it’s payback time. There’s a boatload of refueling, replenishing and damage repair that has to be done — at the very least in my own body, quite possibly in my life as well.

讓我們談談生物標誌物

Let’s talk Biomarkers

希望到現在為止,您可以看到大多數(如果不是全部)所謂的“雙相”症狀與人類的壓力(生存)反應有關。更好的消息是,有一種方法可以測試看看這是否正在發生。這些壓力狀態有許多生物標誌物:血壓、血糖和氧氣水平、血液和唾液中的激素(例如腎上腺素、糖皮質激素)測試、皮膚電導率測試、肌肉緊張或抽搐、運動頻率、是否精細運動或大的運動更普遍,瞳孔擴張,視覺感知是否偏向於細節或粗略印象,腦部掃描以查看哪些神經通路是“熱”或“冷”……不勝枚舉。

Hopefully by now you can see how most — if not all — of the so-called ‘bipolar’ symptoms connect to the human stress (survival) response. The even better news is that there is a way to test to see if this is what’s happening. There are numerous biomarkers for these kinds of stress states: blood pressure, blood sugar and oxygen levels, blood and saliva tests for hormones (e.g., adrenaline, glucocorticoids), skin conductivity tests, muscle tension or twitching, frequency of movement, whether fine motor or large motor movements are more prevalent, pupil dilation, whether visual perception is biased toward detail or gross impressions, brain scans to see what neural pathways are ‘hot’ or ‘cold’… the list goes on.

那麼其他 DSM 障礙呢……?

What about other DSM Disorders…?

是的,他們都可能與壓力反應相關,症狀也與已知的“壓力特徵”相匹配。我們開始繪製它們並進行我們許多人一直呼籲的真實/誠實的科學只是時間問題。

Yep, they all potentially have their stress response correlates, with symptoms that match known ‘stress signatures’ as well. It’s only a matter of time before we start to map them and do the real/honest science that so many of us have been calling for all along.

請繼續關注——我們將在不久的將來從壓力反應的角度揭穿這些其他“障礙”。

Stay tuned — we’ll be debunking some of these other ‘disorders’ from a stress response perspective in the near future.

為什麼這很重要

Why this matters

假設您告訴我,我在“雙極”精神狀態下造成的殘骸是由於遺傳或疾病狀況導致我的大腦結構有缺陷。如果是這樣的話,那麼我對有效治療的任何希望在邏輯上都是腦科學家、醫生和外科醫生的職權範圍。我的主要職責是祈禱他們盡快找到治療方法。

Let’s suppose you tell me that the wreckage I create in a ‘bipolar’ state of mind is due to a genetic or disease condition that renders my brain structurally defective. If that’s the case, then any hope I have of effective treatment is logically the purview of brain scientists, doctors and surgeons. My major role is to pray that they figure out a cure and soon.

另一方面,假設問題根本不是那個問題。假設真正推動我所謂的“狂熱”的是我的壓力/生存反應正在瘋狂地激發。

On the other hand, suppose the problem isn’t that at all. Suppose that what’s really driving my so-called ‘mania’ is that my stress/survival response is firing wildly.

那麼解決方案就在我可以使用的範圍內。是的,我有一些學習要做。我需要了解生存系統如何運作的基礎知識。我需要了解是什麼開啟了它——更重要的是,是什麼關閉了它。

Then the solution is a lot more within the realm of something I can work with. Yes I have some learning to do. I need to understand the basics of how the survival system operates. I need to learn what turns it on — and even more importantly, what turns it off.

但是,如果我掌握了這些基本知識(普通人可以在幾個小時內學會),那麼我可以通過自己的觀察和反複試驗來處理大量的工作。

But if I have that basic knowledge (which the average person can be taught in a few hours) then I have a tremendous amount I can work with through my own observation and trial and error.

與“狂熱”合作

Working with ‘Mania’

以下是我發現對我有用的一些基礎知識。

Here are some basics that I’ve found useful for me.

是什麼讓我興奮?

What turns me on?

生存反應從恐懼開始。捕食者恐懼和獵物恐懼看起來有點不同。掠食者害怕失去機會。獵物害怕成為他們。但恐懼仍然是激活系統的基本觸發器。

The survival response turns on from fear. Predator fear and prey fear look a little different. Predators get scared of losing opportunities. Prey get scared of becoming them. But fear is still the basic trigger that activates the system.

是什麼讓我反感?

What turns me off?

我曾經認為沒有辦法關閉這個東西。從我記事起,它就一直是我的一部分——基本上是我的生活。我無法想像如何使用它。我嘗試了很多東西,但似乎沒有一個真正起作用。毒品讓我心煩意亂,但同時也扼殺了我對自己所享受的一切。我覺得卡住了。

I used to think there was no way to shut this thing down. It had been a part of me — and basically running my life — for long as long as I could remember. I couldn’t imagine how I could work with it. I had tried so many things, none of them really seemed to work. The drugs shut me down, but killed everything I enjoyed about myself along with it. I felt stuck.

當我開始將自己的身體視為盟友而不是敵人時,情況開始發生變化。

Things started to change when I began to see my body as my ally, rather than my enemy.

簡單的事實是:我的身體基本上討厭處於生存模式。生存系統會消耗能量和資源,就像它們已經過時一樣。這根本不可持續。

The simple fact is this: My body basically hates being in survival mode. The survival system burns up energy and resources like they’re going out of style. It’s simply not sustainable.

人體內有300萬億個細胞。生存反應使其中一些供過於求,但使絕大多數高而乾燥。對於這些細胞的其餘部分,生存模式下的生活相當慘淡。當生存系統關閉並運行時,他們的需求基本上都被忽視和得不到滿足。他們對此一點也不高興。沒有什麼比退出生存模式並回到每個人都必須提供的另一種選擇(快樂、可持續、放鬆)更讓他們快樂的了。

There are 300 trillion cells in the human body. The survival response oversupplies a few of them, but leaves the vast majority high and dry. For the rest of these cells, life in survival mode is pretty dismal. Their needs are all basically getting ignored and going unmet while the survival system is off and running. They are not happy about this at all. Nothing would make them happier than to exit survival mode and go back to the other option (happy, sustainable, relaxed) that every human body has to offer.

另一種選擇是副交感神經系統的休息和刷新模式。你對這個系統了解不多。與戰鬥或逃跑相比,這被認為很無聊。它基本上涉及維修和保養。

This other option is the rest and refresh mode of the parasympathetic nervous system. You don’t hear much about this system. It’s considered boring, compared to fight or flight. It’s basically involved in repair and maintenance.

但是,當您考慮它時,這個恢復性的身體系統具有巨大的智慧和潛力。這就是讓我們消化食物、保持穩定的心跳、不忘記呼吸、補充資源和晚上睡覺的原因。它使我們能夠成長、治癒傷害、抵禦感染、繁殖——以及愛和與我們自己、彼此以及任何超越的事物建立聯繫。

But, when you think about it, there is tremendous wisdom and potential in this restorative bodily system. It’s what lets us digest food, keep a steady heartbeat, not forget to breath, replenish resources and sleep at night. It’s what allows us to grow, heal injuries, defend against infection, reproduce — and love and connect with ourselves, each other and whatever is beyond.

更好的是,我們的這個恢復性(副交感神經)部分從子宮開始就與我們同在。它比其他任何人都更了解我們的需求以及如何更好地滿足這些需求。身體中沒有一個細胞離它所管理的毛細血管網絡超過五個細胞。它實際上每天晚上在我們睡覺時對我們進行腦部手術,以治愈白天的傷害。

Better yet, this restorative (parasympathetic) part of us has been with us since the womb. It knows our needs and how to meet them better than anyone else could. No cell in the body is even more than five cells away from the capillary network it manages. It literally does brain surgery on us every night while we sleep to heal the damage of the day.

換句話說:地球上最“笨”的人有一個副交感神經系統,它比任何曾經生活過的神經科學家都要聰明。如果不是這樣,我們現在誰也活不了。

Put another way: The ‘dumbest’ one of us on the planet has a parasympathetic nervous system that is smarter than any neuroscientist who ever lived. If that weren’t the case, none of us could be alive right now.

關閉“狂熱”

Turning Off ‘Mania’

如果我想在這個世界上發揮作用,我的身體基本上給了我兩個選擇:

If I want to function in this world, my body basically gives me two choices:

1. 一種生存(壓力)反應,讓我振作起來,讓我繼續奔跑和追逐。

1. A survival (stress) response that revs me up and keeps me running and chasing.

2. 一個恢復系統(副交感神經系統),它提供較少的興奮,但提供真正的寧靜和可持續性(幸福)的選擇。

2. A restorative system (parasympathetic) that offers less excitement but the option of real serenity and sustainability (well-being).

我個人的信念是: 我必須決定“我想餵哪隻狼”。

My personal belief is this: I have to decide ‘which wolf I want to feed.’

對我來說,這意味著積極地選擇我想要生活在哪個身體系統中,並與作為人類的生活相關聯。它是信任和聯繫的主體——可持續性、恢復和福祉嗎?還是興奮、野心、緊追不捨的身體?

For me, that means actively choosing which bodily system I want to live in and relate to life from as human being. Is it the body of trust and connection — of sustainability, restoration and well-being? Or is it the body of excitement, ambition and hot pursuit?

下定決心建立信任和聯繫機構大約是成功的一半。以下是我發現有用的其他一些技巧:

Setting my mind to go for the trust and connection body is about half the battle. Here are some other tips I’ve found useful:

- 生存(壓力)系統持續存在是有原因的。它向我發出信號,表明我在乎的事情感覺不安全或處於危險之中。一旦解決了該風險,系統就沒有理由繼續運行。一旦我開始感到安全,它就會自然關閉。因此,我通常會著眼於恢復安全感和幸福感來進行激活。我問自己我害怕什麼,並試著誠實地傾聽答案。有時只是做這麼多——誠實地承認我害怕某事並面對事實的真相——會有很大幫助。

The survival (stress) system goes on for a reason. It is signalling me that something I care about feels unsafe or at risk. Once that risk is addressed, the system has no reason to stay on. It turns off naturally once I start to feel secure. As a result, I generally approach my activation with an eye to restoring a sense of safety and well-being. I ask myself what I’m scared of and try to listen honestly for the answer. Sometimes just doing this much — honestly owning that I’m scared of something and facing the truth of what that is — can help a lot. - 有意識地接觸健康的身體(恢復系統)有一點技巧。我無法通過更加努力或強迫自己感受某些東西來訪問我的這一部分。我越努力,我的生存(壓力)系統就越活躍。當我決定放手讓自己得到幫助時,恢復性(幸福感)系統就會啟動。我有意識地將注意力從試圖修復它轉移到積極培養我信任和被關心的能力。這與許多宗教的智慧(以及十二步計劃)相似。我個人的信念是,這不是一次意外,而是更多次。

There’s a bit of a trick to making conscious contact with the body of well being (restorative system). I can’t access this part of me by trying harder or forcing myself to feel something. The harder I try, the more my survival (stress) system revs up. The restorative (well-being) system turns on when I make a decision to let go and allow myself to be helped. I consciously shift my focus from trying to fix it to actively cultivating my capacity to trust and be cared for. This parallels the wisdom of many religions (and also Twelve Step programs). My personal belief is that this is not an accident, but more on that another time. - 作為一個有大量社會創傷的人,並且從歷史上看,我與我的身體關係非常糟糕,要做出這種轉變來之不易。儘管如此,我發現通過實踐是可能的。隨著時間的推移,內部電機已經開始減速。一切不再總是危機。它並不總是必須立即修復 – 有時根本不需要!現在有一種心態,我可以訪問一切真的很好的地方。

As someone with a boatload of social trauma, and a really bad relationship with my body historically, making this shift this has not come easily. Nevertheless, I’ve found it possible with practice. Over time, the internal motor has begun to slow down. Everything is not always a crisis anymore. It doesn’t always have to get fixed right away — and sometimes not at all! There is now a frame of mind that I can access where everything really is okay just the way it is. - 為了減少我花在生存反應上的時間,它有助於學會識別放大的跡象。然後,我可以使用那個“生物反饋”作為正念鈴,回到幸福的身體。一旦回到相對健康的狀態,我就可以開始溫和地調查是什麼讓我害怕,並允許解決它的可能性冒出來。

In trying to lessen the amount of time I spend in survival reactivity, it helps to learn to recognize the signs of amping up. I can then use that ‘biofeedback’ as a mindfulness bell to return to the body of well being. Once back in that state of relative well being, I can begin to gently inquire into what is scaring me and allow possibilities for addressing it to bubble up. - 總而言之,有無數種讓你感到害怕的方式,但也有無數種讓你感覺更安全的資源。還有無數種選擇可以找到我可以信任的東西或人。這就是地球上生活和經驗的多樣性是一項巨大資產的地方。

The long and the short of it is that there’s a zillion ways to feel scared, but also a zillion resources for feeling safer. There’s also a zillion options for finding something or someone I can potentially put my trust in. That’s where the diversity of life and experience on planet earth is a huge asset. - 它還可以幫助做一些讓我的身體和我體內的細胞放心的事情,即我們沒有陷入危機。我試圖找到與自己完全不同的方式來與自己相處,如果我從熊身邊逃跑,我的身體會如何表現。這包括緩慢而有意識地移動,激發我對小事的好奇心,做一些需要精細運動協調而不是大肌肉群的事情,一次用一根手指做微小的輕柔觸摸動作,一次一隻腳趾擺動我的腳趾,做一些熟悉的事情就像鋪床、洗盤子、彈吉他一樣簡單……可能性是無窮無盡的。

It can also help to do things that physically reassure my body and the cells in me that we are not in crisis. I try to find ways to be with myself that are totally different from how my body would act if I were running from a bear. This includes moving slowly and intentionally, activating my curiosity about small things, doing stuff that takes fine motor coordination instead of large muscle groups, making tiny gentle touching movements one finger at a time, wiggling my toes one toe at a time, doing something familiar and easy like making my bed or washing a dish, playing my guitar… the possibilities are endless. - 保持耐心很重要。正如薩波爾斯基所指出的,從生存(交感神經)激活到恢復健康(副交感神經)的轉變是一個微妙的過程。兩個系統同時觸發對身體不利(比如心髒病發作不好)。此外,從血液中清除一組激素並引入新激素需要一段時間。因此,身體需要時間進行安全過渡。這需要一段時間——至少 10 到 20 分鐘,更有可能是一兩個小時。有時,當我真正情緒化時,我什至發現它在幾天內慢慢發生。

It’s important to be patient. As Sapolsky points out, the transition from survival (sympathetic) activation to restorative well being (parasympathetic) is a delicate one. It’s bad for the body to have both systems firing at the same time (like heart attack bad). Also, it takes a while to clear one set of hormones from the bloodstream and introduce new ones. Thus, the body needs to time to make a safe transition. This takes a while — a minimum of 10-20 minutes, and more likely an hour or two. Sometimes, I even find it happening slowly over several days when I’ve been on a real emotional bender. - 等待這種轉變會讓人感到非常不舒服。我越活躍,通常就越難坐穩。但是,如果我能夠繼續信任這個過程(而不是驚慌失措並讓自己重新陷入壓力反應),我的身體會逐漸變得更加舒適。我的肌肉放鬆,因為我的心血管和內分泌系統停止抽水並為它們做準備。循環系統開始將氧氣和葡萄糖重新輸送到我的胃、腸、胰腺、腎臟和前額葉皮層。當我的消化系統重新啟動到相對平靜的環境中時,噁心、渴望和腸道不適都消失了。理性能力回歸,大局觀和判斷力隨著我的大腦越來越多的工作而徹底提高。最終結果是,我逐漸對休息、放鬆、睡眠、健康食品、娛樂、平凡的社交互動和生活管理任務產生了興趣並能夠享受。我的身體修復和恢復。

Waiting out this transition can feel really uncomfortable. The more activated I am, generally the harder it is to sit tight. But if I’m able to keep trusting in the process (instead of panicking and ratcheting myself back into stress reactivity), my body gets progressively more comfortable. My muscles relax as my cardiovascular and endocrine systems stop pumping and priming them for action. The circulatory system starts re-routing oxygen and glucose to my stomach, intestines, pancreas, kidneys and prefrontal cortex. Queasiness, cravings and gut discomfort dissolve as my digestive system reboots into a context of relative calm. Rational capacities return, and big picture perspective and judgment radically improve as my brain has increasingly more to work with. The end result is that I become progressively interested in — and capable of enjoying — rest, relaxation, sleep, healthy food, recreation, mundane social interactions and life management tasks. My body repairs and restores.

最終我再次感受到了人性。

Eventually I feel human again.

以下是我用來幫助我完成過渡的一些步驟。我每天練習它們,通常通過設置計時器並將它們作為冥想進行(例如,每步 1-2 分鐘)。

Below are some steps that I use to help me make the transition. I practice them daily, often by setting a timer and doing them as a meditation (e.g., 1-2 minutes per step).

如果我願意嘗試的話,它確實有效。

It actually really works, if I’m willing to try it.

- Sapolsky, R. (2017)。行為:人類的生物學在我們最好和最壞的情況下。紐約:企鵝出版社, https ://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/19107284-d0wnload-behave-pdf-audiobook-by-robert-m-sapolsky (第 194-95 頁)。

Sapolsky, R. (2017). Behave: the biology of humans at our best and worst. New York : Penguin Press, https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/19107284-d0wnload-behave-pdf-audiobook-by-robert-m-sapolsky (pages 194-95). - Sapolsky, R. (2004)。 為什麼斑馬沒有潰瘍,第 3 版(紐約:Holt 平裝書), https ://www.mta.ca/pshl/docs/zebras.pdf 。

Sapolsky, R. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, 3rd Edition (New York: Holt Paperbacks), https://www.mta.ca/pshl/docs/zebras.pdf. - Bradley, MM, Codispoti, M., Cuthbert, BN 和 Lang, PJ (2001)。情緒和動機 I:圖像處理中的防禦和食慾反應。情感,1(3),276-298。 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/cd1a/a512069ea32d00bba9e2d9e62f172304652f.pdf。

Bradley, M. M., Codispoti, M., Cuthbert, B. N., & Lang, P. J. (2001). Emotion and motivation I: Defensive and appetitive reactions in picture processing. Emotion, 1(3), 276-298. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/cd1a/a512069ea32d00bba9e2d9e62f172304652f.pdf. - Bradley, MM & Lang, PJ(印刷中)。動機和情感。在 JT Cacioppo、LG Tassinary 和 G. Berntson(編輯), 《心理生理學手冊》(第 2 版)中。紐約:劍橋大學出版社,http ://brain-mind.med.uoc.gr/sites/default/files/aaaaEmotion_0.pdf ,

Bradley, M. M. & Lang, P. J. (in press). Motivation and emotion. In J.T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, and G. Berntson (Eds.), Handbook of Psychophysiology (2rd Edition). New York: Cambridge University Press, http://brain-mind.med.uoc.gr/sites/default/files/aaaaEmotion_0.pdf, - Lang, PJ 和 Bradley, MM (2010)。情感和激勵大腦。生物心理學,84(3),437-450。 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3612949/pdf/nihms-164194.pdf

Lang, P. J., & Bradley, M. M. (2010). Emotion and the motivational brain. Biological Psychology, 84(3), 437–450. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3612949/pdf/nihms-164194.pdf - Lang, PJ 和 Bradley, MM (2013)。食慾和防禦動機:目標導向還是目標確定?情感評論:國際情感研究學會雜誌,5(3),230–234。 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3784012/pdf/nihms452994.pdf

Lang, P. J., & Bradley, M. M. (2013). Appetitive and Defensive Motivation: Goal-Directed or Goal-Determined? Emotion Review : Journal of the International Society for Research on Emotion, 5(3), 230–234. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3784012/pdf/nihms452994.pdf - Schupp, H.、Cuthbert, B. 等人。(2004 年)。情緒感知中的大腦過程:動機性注意力、認知和情緒,18:5, 593-611, http://wwwtest.kch。uiuc.edu/Research/Labs/neurocognitive-kinesiology/files/Articles/Brain_ processes_in_emotional_perception_Motivated_ attention.pdf _ _ _

Schupp, H., Cuthbert, B., et al. (2004). Brain processes in emotional perception: Motivated attention, Cognition and Emotion, 18:5, 593-611, http://wwwtest.kch.uiuc.edu/Research/Labs/neurocognitive-kinesiology/files/Articles/Brain_processes_in_emotional_perception_Motivated_attention.pdf

莎拉·克努森http://peerlyhuman.blogspot.com/Sarah Knutson 是一名前律師、前治療師、倖存者活動家。她是 Peerly Human (http://peerlyhuman.blogspot.com) 和 Wellness & Recovery Human Rights Campaign 的組織者/博主。莎拉為普通人組織了免費、同行經營、同行資助的機會,以提供、接受、分享和體驗無條件人格和我們自己真實、脆弱的人性的根本變革力量。